All troops would be withdrawn from the country within 60 days.

The announcement on Jan. 27, 1973, drew mixed emotions from the 500,000 Americans who fought in the nearly decade-long war. More than 58,000 Americans were killed and 150,000 were seriously injured.

A clear victory hadn’t been reached.

View a slideshow of photos from the war. ‘More work to do’ In 1970, Jim Weatherbee’s commander gathered his team in the officers’ club in Pleiku, where the 32-year-old had been serving as a forward air controller for about a year.

Weatherbee and his team of 30 Cessna 0-2 Skymaster pilots had been running reconnaissance seven days a week, 12 hours a day for the U.S. and South Vietnamese Army Special Forces troops on the ground.

If the troops came under fire, they’d fly in and lay rockets as markers for fighter planes coming through to stop the firefight by dropping bombs or napalm.

The Cessnas were under constant fire from the ground. Weatherbee had been hit twice. He said he was careful not to get hit again or he’d have been grounded from flying.

That day at the officers’ club, Weatherbee’s commander told him they would be turning over all operations to the South Vietnamese Army. They would be left to fight the North Vietnamese on their own, a process called Vietnamization that had always been a goal.

Minutes after the announcement, a rocket was fired into the club and the roof was blown off.

“We still had some more work to do,” Weatherbee said recently at his home in Fort Walton Beach.

Despite that, he and his unit were sent to Thailand. By the end of 1972, he was flying reconnaissance for the B-52s that were trying to bomb Hanoi into submission, he said.

That would turn out to be a turning point for the United States. After the bombing, Nixon quietly negotiated with the North Vietnamese and in January announced they had reached an agreement to end the war.

The problems that plagued the South Vietnamese Army in their fight to stave off the North Vietnamese in Pleiku when Weatherbee’s mission was called off in 1970 were still there after the war was declared over, Weatherbee said.

“I thought it was an appropriate thing to do (to end the war), but when we do that you have to leave something in place that can defend itself,” he said. “Unfortunately, as soon as we withdrew, the South Vietnamese just couldn’t handle it.”

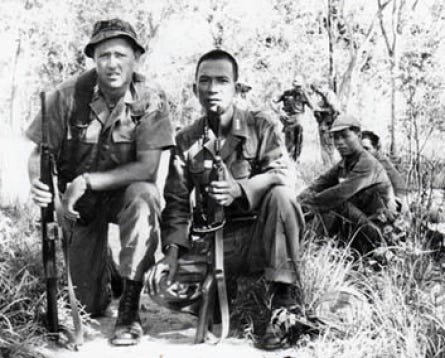

The North Vietnamese had taken over Saigon by the end of 1975. A waste of lives In 1966 Johnnie Prichard, who was in his 30s and serving in the Army, was sent to the jungle as an adviser to the South Vietnamese Army.

“It was unfortunate, or I thought it was, that I wasn’t with an American unit,” Prichard said recently at his home in Bluewater Bay. “You’re out there by yourself and it’s not like having your buddies here on each side of you.”

He said he didn’t sleep for a week until he was too tired to stay awake any longer. He was afraid.

“I had nobody around I’d ever even seen before in my life,” he said.

As Prichard slogged through the hot, steamy jungle, he toted a short automatic rifle, his ammunition, four canteens of water strapped around his waist, several grenades and an unwieldy radio.

He lost 50 pounds in the first six months, he said.

“It was 114 degrees in the morning,” he said. “It didn’t take you long to lose any excess weight.”

The brutality he saw was hard to recover from.

When he arrived in Saigon, before he even got into the jungle, he saw a firing squad kill several Vietnamese soldiers in the street.

At one point after he was embedded with the South Vietnamese in the jungle, the squadron split up for a mission. However, one of the companies had been infiltrated by about 50 Viet Cong soldiers, Prichard said.

“When they got off by themselves, they lined that company up and took the officers and shot every one of them between the eyes,” he said.

The effects of the war continued long after then-Maj. Prichard returned home.

He avoided windows, and when he heard a loud noise he would find himself on the floor. One time his wife woke him and he jumped up and knocked her to the ground.

“It took awhile to get over that, but you work on it,” he said. “You just work on it.”

When Nixon announced the end the war, Prichard said he thought it was great.

“After I was over there, I thought it was a waste of 58,000 soldiers and blood and all that money,” he said. “It wasn’t a betterment for anybody. All we did was delay what was inevitable.”

An unhappy camper Retired Maj. Gen. Dick Secord was in the Pentagon by the time Nixon declared an end to the war in 1973, but he started out seven years earlier as one of the first U.S. troops in Vietnam.

In 1966, Secord was serving with an elite Special Forces group, the Jungle Jim operation that trained at Hurlburt Field. They were stationed at Bien Hoa Air Base near Saigon. Secord flew an AT-28 single-engine plane carrying 3,500 pounds of ordnance, napalm cans, gun bombs and pods of rockets. They were pummeling targets on the ground.

Vietnamese soldiers rode in the back seats; the missions officially were registered as training flights if any of the planes went down.

They were under constant fire and many planes got hit, Secord said.

“But not mine, thank God.”

More than 20 airmen from the elite operation were killed in the first two years of the war.

When Nixon announced the end of the war, Secord was working in the Office of the Secretary of Defense at the Pentagon.

He was extremely disappointed. “I was not a happy camper,” he said.

The United States had just completed the Linebacker II bombing campaign in North Vietnam, and Secord felt that militarily they had the upper hand.

“The North Vietnamese were pounded into a frazzle and they gave up,” he said. “Nixon and (Henry) Kissinger decided to call it off after that, but I think history shows they should have kept it up for a while.” No need to be there In 1972, Bob Welty, then 21 years old and serving in the Air Force, was stationed in Da Nang as a radar mechanic for F-4D phantom jets.

He and his crew worked 12-hour shifts to prepare the planes for constant bombing missions.

Every third night or so their base came under rocket attacks, Welty said.

They knew the rockets were coming because the dining hall that day would only have plastic utensils, a sure sign that the locals had not come to work because they had been tipped off.

Welty, now 62 and living in Fort Walton Beach, described what he felt after he heard the rockets being fired as “five seconds of sheer terror.”

“In six months, that’s 50 nights of ducking,” he said. “You’d stay up all night waiting for them and then get down on the ground and kiss your ass goodbye or smile because you were safe … I saw a lot of people get hurt.”

Welty said he did what he was asked to do in Vietnam, and at the time he was proud of the work he did, but many years later his views started to change.

“I was all gung-ho and for the war when I went over. I was 21, 22 years old. I was a kid,” he said. “Now I think we were pretty terrible and of how many people I was responsible for killing. But, back then we were doing our job.”

He said when Nixon announced the end of the war he knew it was good to get out of Vietnam.

“This is so ridiculous,” he said he thought at the time. “Why did we even get involved? We didn’t even need to be there.”

Contact Daily News Staff Writer Lauren Sage Reinlie at 850-315-4440 or lreinlie@nwfdailynews.com. Follow her on Twitter @LaurenRnwfdn.

This article originally appeared on Crestview News Bulletin: 40 years after ‘peace with honor’ (GALLERY)