Income inequality and the minimum wage have become national buzzwords, but noticeably absent from the conversation is the economic plight of American farmworkers.

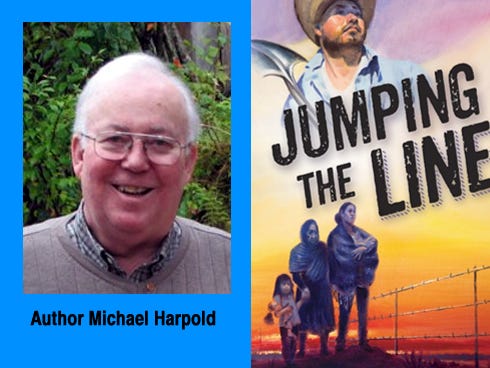

“Almost half the people laboring in our fields are U.S. citizens and legally authorized immigrants, but Americans tend to think they’re all illegals, so they accept the situation,” Michael Harpold said. Harpold is a 35-year veteran of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service and author of the new book “Jumping the Line,” (www.jumpingtheline.com) a realistic and dramatic portrayal of an illegal immigrant and a Mexican-American farmworker family.

“We’re terrified food prices would skyrocket — a fear perpetuated by some in the agriculture industry — if we don’t keep the lid on labor prices.”

Ask the farmers and they’ll say, “I’m paying far more than the minimum wage,” and that’s often true, Harpold says. “What’s not said is that the work is seasonal, so the laborer works only 100 days a year. His annual income falls far below the poverty line.”

Non-supervisory farmworkers earned an average hourly wage of $10.80 in 2012, well over the federal minimum wage of $7.25, according to the Farm Labor Survey conducted by the National Agricultural Statistics Service.

The same survey found nearly half did not have year-long jobs.

The impact of extreme poverty on farmworkers — more than 2 million, including undocumented immigrants — affects all of us.

“Imagine how well local businesses would do if these workers had enough money to dine in their restaurants, visit their shops and pay for their services,” Harpold says. “Imagine the benefits to us all if their children could stay in one school for a full year, and if they could aspire to careers beyond the fields.”

If we could stem the flow of cheap labor crossing illegally into our country, and if we relied only on legal immigrants and citizen workers, wages would rise, he says.

What would that look like for the rest of us? Harpold says it’s not the frightening picture some stakeholders paint.

•We’d pay less than $1 more a month for produce. According to University of California at Davis agriculture economist Phillip Martin, a 40 percent increase in farmworker wages would translate to a 2 to 3 percent increase in retail prices for fruits and vegetables. The trade-off is less economic cost borne by government to support impoverished farmworker families.

•We would curtail the creation of more substandard jobs in agriculture. Guest worker programs — where foreign workers are invited to work on U.S. farms — perpetuate pockets of rural poverty by keeping labor costs low, encouraging the creation of more low-skilled, low-income jobs in the area. Pending House and Senate legislation proposes to allow in hundreds of thousands of new guest workers. If enacted, this will continue the vicious circle of poverty and inadequate education trapping immigrant farmworker families striving to assimilate in our society. Children of immigrants living in two-parent families are twice as likely to be poor (44 percent versus 22 percent) as the children of natives. Two-thirds of farmworker children who live with both parents remain poor. ¹

•Growers will (as they have in the past) innovate to make up for fewer workers. When forced to compete for labor such as occurred when the United States stopped the importation of Mexican farmworkers in 1964, growers innovate, mechanizing harvests, planning crop cycles to coincide with worker availability, and providing housing or transportation. Then, growers signed contracts with farm workers union president Cesar Chavez containing hire back clauses for migratory workers, raising wages and providing healthcare. The brief golden age for American farmworkers ended after a decade and a half because the U.S. failed to stop illegal immigration.

As a nation, Harpold said, we cannot talk about income inequality and minimum wages without including immigration in the conversation.

“It’s all tied together,” he says. “When we address immigration, we will also address persistent poverty for a large segment of the population.”

Michael G. Harpold, author of “Jumping the Line,” began his 35-year career in the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) as a Border Patrol Inspector. Early in his career, he met César Chávez and Harpold’s involvement with farm workers during the grape strike led to a lifelong interest in their plight. He served two years in Vietnam with the U.S. Agency for International Development and, after returning to his job at INS as an employee representative made frequent appearances before congressional committees testifying on proposed immigration legislation and the INS budget. Harpold served five years in the U.S. Army and attended West Point. He holds a bachelor’s degree from California State University at Fresno and attended Golden Gate University School of Law in San Francisco.

¹ The New Rural Poverty, Philip Martin, Michael Fix & J. Edward Taylor, The Urban Institute Press, 2006.

This article originally appeared on Crestview News Bulletin: If farmworkers earned more, could we afford what they pick?