Editor's Note: This originally appeared in the Destin Log in 2001 and the News Bulletin in 2010.

The writer, the News Bulletin's circulation manager, has since updated it.

I arrived in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia in the middle of the night in early January 1991, carrying my baggage and chemical warfare gear. We were herded onto a bus and driven into the dark night, deep into the desert.

The Air Commando compound was a collection of tents and pre-fab buildings. It was virtually pitch black. I was directed to tent D-4 and stumbled inside. A single un-shaded light bulb lit the interior, which was divided by makeshift walls of mosquito netting and ponchos and blankets. Muffled snoring came from behind those cubicles. I found an empty cot and dropped my gear by it. I had found my new home for the better part of the next six months.

The Gulf War, Desert Storm, was still a week or so away then. President George H.W. Bush had given the Iraqis a deadline to withdraw from Kuwait, but no one was certain what they would do. Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein could decide to launch his Scud missiles against coalition forces massing on the Saudi border at any time. We were in a heightened state of alert — our chem warfare gear was never far away, but we weren't carrying it on our persons.

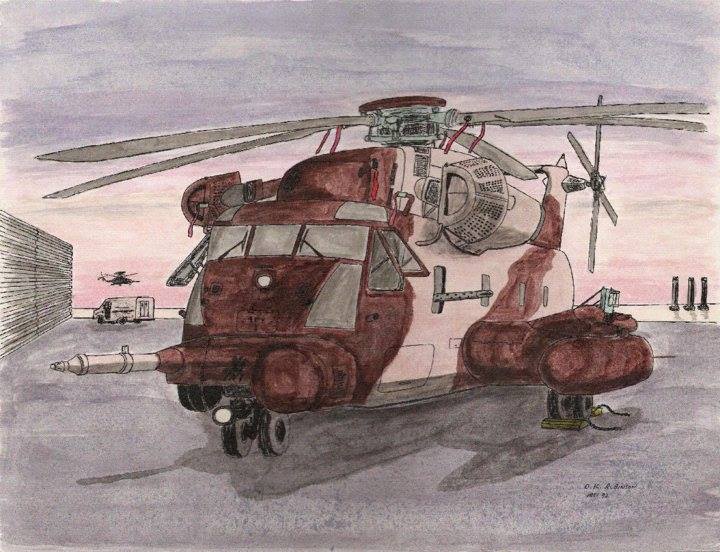

I was on the flight line, working on one of the huge MH-53J Pave Low helicopters that my squadron, the Green Hornets, flew. It was hot and sunny, and I had just clambered down from the top of the chopper when the siren went off. A voice boomed over the loudspeaker system: "CONDITION RED, CONDITION RED!"

That meant that a missile launch had been detected!

I was more scared then than I had ever been before or ever have been since. My chem warfare gear was across the flight line in the terminal facility we were working out of. I ran for my gear as fast as my short, chubby legs would move, and ducked into the terminal as the doors closed. I pulled out my gas mask and slipped it on, clearing and sealing the mask and positioning the hood to protect my head. Sweat poured into my eyes and pooled in the mask. My heart was racing as I waited for whatever might happen next.

Would it be the explosion of a Scud warhead filled with chemical or biological agents?

Instead of explosions, the "ALL CLEAR" sounded. The alert had been a false alarm, a software glitch somewhere. It took a while for my heart rate to subside, but I was never too far from my chem gear after that.

That had put the fear of God in me.

There was one other time I was really frightened. The war had been going for several weeks, and it was a night like most had been. The siren went off and the loudspeaker announced "CONDITION RED, CONDITION RED!" — we could nearly set our clocks by it. We called it our nightly wake up call, since we had to get up for our duty shift anyway. The “ALL CLEAR” usually would come before we finished getting into our gear; the missiles were never aimed at us. Dhahran and Riyadh were the usual targets.

But this night wasn't like the others. As we finished getting into our chem gear and started to saunter out of our tents to the bunkers, instead of getting the "ALL CLEAR" signal, there was a loud explosion and the ground shook.

A Scud had landed about 5 miles from our compound. It took a long time for the "ALL CLEAR" to come that night, since the bomb disposal and disaster preparedness folks had to check it out to ensure that there was no danger from chemical or biological agents.

The Gulf War was unlike any before and probably unlike any in the future. We were lucky that American casualties were light, but I was on duty the night that Spirit 03, an AC-130 gunship, went down with 13 fellow Air Commandos aboard.

It was a sobering time. Our own Pave Low helicopters roamed deep behind Iraqi lines, as close as 60 miles from Baghdad, inserting and resupplying Special Forces troops, and performing search and rescue missions.

Aboard those choppers were people I knew and worked with. The loss of Spirit 03 really brought the realities of war home to us — it could have been someone we knew or even one of us but for the grace of God.

I came home from Saudi Arabia in July of 1991, safe and mostly sound — a welcome anniversary present for my wife.

It had been a long six months in the desert, a lot of hard times; a few good times. I was proud that I had done my part for freedom, proud of the men and women I worked with.

It’s hard to believe that 25 years have passed since then. The Pave Low has been retired to museums and the Boneyard. It was an amazing aircraft, some with more than 40 years of service and flying combat missions until the day they retired.

My squadron, the 20th Special Operations Squadron, moved to Cannon AFB, NM and now flies the CV-22 Osprey.

Most troops I served with have retired. I got to see some of them and swap war stories with fellow Green Hornets during a reunion a few years ago. Facebook has helped me reconnect with many of them as well.

The war stories get better every year! Once a Hornet, always a Hornet!

Dale Robinson is the News Bulletin's circulation manager and a Crestview resident.

This article originally appeared on Crestview News Bulletin: ROBINSON: Remembering the Gulf War